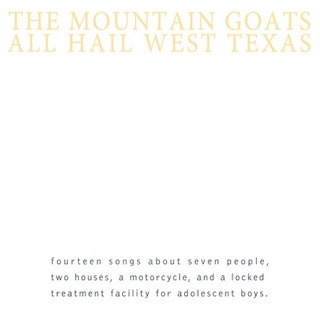

2002: All Hail West Texas

Start a sentence without any idea of how you’re going to wrap it up. Then sing/say whatever you’ve got over a beat you like; accompany it with some simple chords. (Or the other way around: start with the music and improvise the line.) Start another sentence (it can be related to the first one but it doesn’t have to be) over the same beat and chords (change them up if they’re not doing enough to the pleasure centers in your brain). Keep going until you sort of feel what’s going on and use that feeling to expand the frame. Press toward a point of completion that you’ll never actually reach. Revise and adjust until you feel pretty good about far you’ve actually come. Hit record.

It’s at least something like that, I think, the way that Darnielle wrote his songs back in circa 2000.1 Like when he wrote “The Mess Inside,” in mid- to late-2000, just before The Coroner’s Gambit came out.

The version of the song that appears on All Hail West Texas, which was released in February 2002, makes it seem like the super-simple chord progression—G5, Csus2—strummed mostly unmuted, came first. Over a DAH-DAH-dah-da-dah-d’ beat (which he mixes up, obviously), he tosses out a promising-seeming line over a bar of G5 (We took a weekend, drove to Provo), adds a holding-pattern line over a bar of Csus2 (The snow was white and fluffy), steps back for a comment on the action (But a weekend in Utah won't fix what's wrong with us), and then steps forward into a description that bellies out a little, poetically and conceptually (The gray sky was vast and real cryptic above me). He lifts into a frame-expanding pre-chorus—“I wanted you/To love me like you used to do”—and then, within that larger space, goes back to the situation that he’s established and begins the second verse. Not much changes in what follows; there are more verses than usual (four!) but no narrative development, just a thickening of the situation. And in the outro, Darnielle just plays the two chords in a sort of stately way, slows down, and stops. We’re left not to process a story but to stay with a scenario, a scenario that arises from and sinks back into empty, open space.

The other thirteen songs on All Hail West Texas have the same spell-like feel, the same feeling of incantation (from the Latin in-cantare, to sing, to bewitch) and enchantment (same etymological root). Each track begins and ends with a rrWOWrr or two of wheel grind, which is part of the source of that effect, for me. And there are no overdubs and no instruments other than an acoustic guitar and (in one case) a Casio, so each song is a kind of conjuration, an instance of one person trying to make one thing happen at one time. In a 2006 interview, Darnielle said of the German techno-pop artist Barbara Morgenstern that “sonically, obviously, she’s in a totally different world, but to be a big hippie about it, the point of origin is the same: that human impulse to make a song where there wasn’t anything before.” You can sense that impulse in every song Darnielle ever recorded, but in the songs on All Hail West Texas, you can sense it in something close to a state of purity. When you say “West Texas,” it evokes, for most people, a vast flatness, a denuded, dry expanse. Titling an album All Hail West Texas—and giving it a mostly white cover—is, maybe, a way of signaling your respect and gratitude for the nothingness out of which songs and other artworks emerge, for the vanishing that makes it possible to appear.

It’s also a way of underscoring the pervasive feeling of loneliness in the songs. “Many of my songs take as their springboard the pain of separation,” he told an interviewer in 2002. “Being separated from people or places or things is always hard.” In early 2001, he had taken a job as a counselor at Beloit-Lutheran, a residential psychiatric treatment facility for young people, and during orientation, with Lalitree gone (at hockey camp), he had started writing and recording after work, in a state of intensified separateness.2 The All Hail West Texas songs have the feel of that separateness in them. The central characters—a pair of teenagers named Jeff and Cyrus who are punished for their metal-stardom dreams (“The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton,” saved for later); a high-school running back who gets hurt, stops playing, sells acid to a cop, and gets punished for it (“The Fall of the High School Running Back”); a bunch of broken people who come to a house where they can get drunk and high without having to talk to anyone (“Color in Your Cheeks”); a couple who can’t give up on a relationship that no longer gives them what they need (“Fault Lines,” “Balance,” “Riches and Wonders,” “The Mess Inside”); and someone in love with a woman who disappears (“Jenny,” “Source Decay”)—are defined by losses that have sort of frozen them in place. Life still demands what it demands inside them, and they’re still mostly beauty-drawn and love-ready, but there’s a massive centripetal force that seems to be locking them down in west Texas: they occasionally make quick trips out of state (Vegas, Provo, New Orleans, New York, the eastern edge of New Mexico), but they mostly stay right there. The album’s last song, “Absolute Lithops Effect,” is named after a plant that looks like a rock, something that seems non-living but is secretly alive.

The room-bound speaker, feeling the life in him, imagines that his “season of waiting” is coming to an end, that he’s about to “find the exit,” but he’s just imagining it: the song, and the album, end before it happens.

The only reason why you might think that it will happen, that the “tender mercy” that he’s wishing for will come, is the way that Darnielle sings the phrase “tender mercy”: with real propitiating feeling, “TENder . . . MERcy,” twice in a row, over a E-Bm and then over an A-E. It’s a hard-to-resist chord progression, one that evokes, simultaneously, a blues-rock E-D-A-E and a folk-style E-B-A-E, and it’s like a breath of fresh air after the moody, dissonant prechorus (E-Cmaj7-E, E-Cmaj7-E). There’s no verbal rejoinder to the pain of separation on All Hail West Texas, no compensatory uplift in the lyrics, but there are, all the way through it, breath-of-fresh-air sequences like that one. For instance: if you’re playing a major key song and are shifting to the pre-chorus or chorus, it usually sounds and feels good to go to a IV-V-I-IV progression, in which you build up to the tonic chord (the chord that matches the key of the song) by means of a chord based on the fourth note in the scale and a chord based on the fifth note in the scale, and then, after reaching the tonic chord, fall back to the fourth-note chord. In each of the couplets below, the first line is played over a IV-V and the second line is played over a I-IV (each of the chords is struck on the capitalized syllable or beat):

And THIS was how Cyrus got SENT to the school

Where they TOLD him he’d never be FAMous (“The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton”)

And she came HERE after MIDnight

The HOT weather made her FEEL right at home (“Color in Your Cheeks”)

<BEAT> Nine hundred cc’s of RAW whining power

<BEAT> No outstanding warrants for my arREST (“Jenny”)

And WHAT will I do with YOU

Pink and BLUE, true GOLD (“Pink and Blue”—there’s a passing chord here on “true”)

I WANTed YOU

To LOVE me like you used to DO (“The Mess Inside”)

<BEAT> Old issues of SUNset

MagaZINE to read (“Jeff Davis County Blues”—the second IV chord comes a line later)

I WAITed for YOU

But I NEVer told you where I WAS (“Distant Stations”)

And I PARK in an alley and READ through the postcards

You conTINue to SEND (“Source Decay”)

Darnielle obviously doesn’t mind if we notice that over half of the songs on the album have identical hooks; one thing you can say for sure about All Hail West Texas is that he’s not trying to score novelty points, musically. It’s much more important to him, I think, that we feel how sustaining that simple rise-reach-reset sequence can be. Or, in these two couplets, how satisfying a self-contained V-IV interlude can be:

I am HEALTHy, I am whole

But I have POOR impulse control (“Riches and Wonders”)

I am FAR from where we live

And I have NOT learned how to forgive (“Blues in Dallas”)

Sometimes you just need to jump on what will help you get where you need to go—sometimes it doesn’t matter whether you or anyone else has jumped on something like it before.

Sometimes it’s even better if you’ve used it a lot before. “If you’re just rocking a 1/4/5, you can get out of your head a little because your hands will already know what they’re doing,” he says in a 2007 interview. “You can’t wash a dish if you’re thinking, ‘How now shall I wash this dish?’ You gotta just put the damned thing in the soapy water and get on with it.” By writing songs in a way that makes it easier to fall into a state of improvisatory creativity, he makes it possible for himself to elaborate on his narratives a little more, to write songs that are like super-short stories. In “Source Decay,” for example, we find out in the first verse and chorus that the speaker drives two hours to Austin every week to check an old P.O. box for postcards from his ex-girlfriend; that whenever a postcard arrives, he parks in an alley in their old neighborhood to read it; and that when she asks him what he remembers, the only thing that comes to his mind is “the train headed south out of Bangkok/Down toward the water.”

One evening, while driving west from Austin into the setting sun’s glare and wishing he could just drive like that forever, his heart breaks, with a hard snap. He makes it back to his house, lies on the ground in his front yard for a while, and then goes inside to the kitchen, where he sorts and studies the postcards, hoping to figure out where she is. But he can’t, she’s gone, that’s all there is to it. And then the train headed south out of Bangkok rushes back into his mind, the train headed “down, down toward the water,” which now feels like the place into which each of our most cherished experiences is flowing, into which each of them will eventually disappear. It’s not a I-IV-V song—there’s a II and a VI in there—and four bars drop out of the second verse, but it’s still pretty simple, and it does seem to have made it possible for him to get out of his head a little, to do a little more than usual with the story that he experimentally began.

“What you come away with from a book for me is never a point or a moral, you know,” Darnielle said during a 2009 interview with the writer Tobias Woolf. “It’s a tone. It’s the feeling you get after you go out dancing all night and you come home and you can’t really say, because you’ve been drinking, you know, you can’t say what songs they played, as you’re walking home, but you know how you feel.” All Hail West Texas has a tone like that. There’s a “sheen” to it, a “shimmer,” a “light that comes off it, like the heat coming off a road.” The heat coming off it is . . . the human impulse to make a song where there wasn’t anything before. Loneliness. The longing for tender mercy. Whatever it is, I sense it, even though I couldn’t technically point it out. All I can do is conjure up impressions of what Darnielle conjured up on this album, to evoke the place or state that the songs seem to rise from. “I think the experience of making music and playing music is so antithetical to the way we try to describe, you know, ‘Here’s what happened, and here’s what it meant,’” Darnielle said in 2013. “A lot of those things [in my songs] happened before there was any ‘why,’ and anything after the fact is maybe over-analytical.” Two nights ago, I saw Darnielle play a solo show, and under-analysis feels right. It’s more than enough to know, as you’re walking home, how you feel.

“I’m ad-libbing when I write, half the time. I’m playing something on the guitar and just barking stuff out loud. Singing stuff, whatever comes to mind, and when something grabs me, I’ll grab a notebook, and keep the guitar on my lap and start jotting things down. But I can’t imagine going “Well, let me tell the story of a guy who owns a grasshopper,” or whatever. If I did that, it would feel forced, and the whole point of what I do is to sound spontaneous.” . . . “I don’t pose a question and then write to get an answer. I write, and then figure out the question I was trying to answer. If it is a question. Sometimes it’s a cool story. The story tells me what it’s about. I tell a story, or paint a picture, or set a scene. What I’m interested in in the scene is what I gravitate toward.” . . . “Dark little webs. If there’s anybody reading this who hasn’t gone down to the bottom of the well with Joni Mitchell, this is the key: these are not introspective singer-songwritery meditations on life, etc. They may be autobiographical; they probably are; but what does it matter? The whole point is the tension between introspection and the necessary distance between oneself and the work that lies ahead. The point is that this very tension manufactures its own kind of darkness, and that this is a vicious circle from which there is no escape.”

“[T]he album exists partly because I ended up spending a fair bit of time alone in the house. My wife, Lalitree, was playing hockey with a squad at ISU [Iowa State University], and she heard something about a women’s hockey camp in Banff; it was a week-long deal in summer, and she decided to go. I’d just changed jobs, and I was going through orientation. Orientation, if you’ve already been through it in several health-care jobs, involves getting a bunch of mimeographed handouts which the management is legally required to read to you as you read along. There’s at least five eight-hour days of this, and sometimes it goes on for two whole weeks. You can get a lot of lyric-writing done in the margins of these handouts.

Around three o’clock each afternoon, orientation would let out, and I’d go home to a mainly empty house. (“Mainly” here because I mean no disrespect to the cats, and because I am so poor at housekeeping that no house with me in it can fairly be called “empty.”) I didn’t own a laptop and I’m pretty sure we were still tethered to the wall at 64kbps, so hanging out online all day was even less rewarding than it is now. Some people would have taken this opportunity to hang out with friends, but... like... have you ever seen a possum on a summer night? How he just comes shuffling out of nowhere all by himself, all beady-eyed and content and solitary, heading through the dark to who knows where? I am essentially a possum.

So I’d watch baseball or old horror movies on cable and go through my notes, and I’d mute the TV when I found something I wanted to work on, which had been my songwriting pattern since 1991. I would revise the verses I’d written down on the orientation materials, and set them to music, and record them. Sometimes I’d run down to Hy-Vee for provisions, and listen to my recent efforts on the way there.” (Darnielle, from the booklet in the 2013 reissue of All Hail West Texas)