Introduction

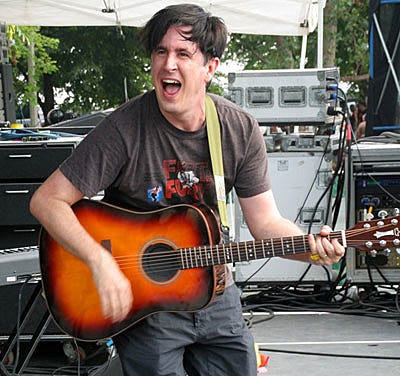

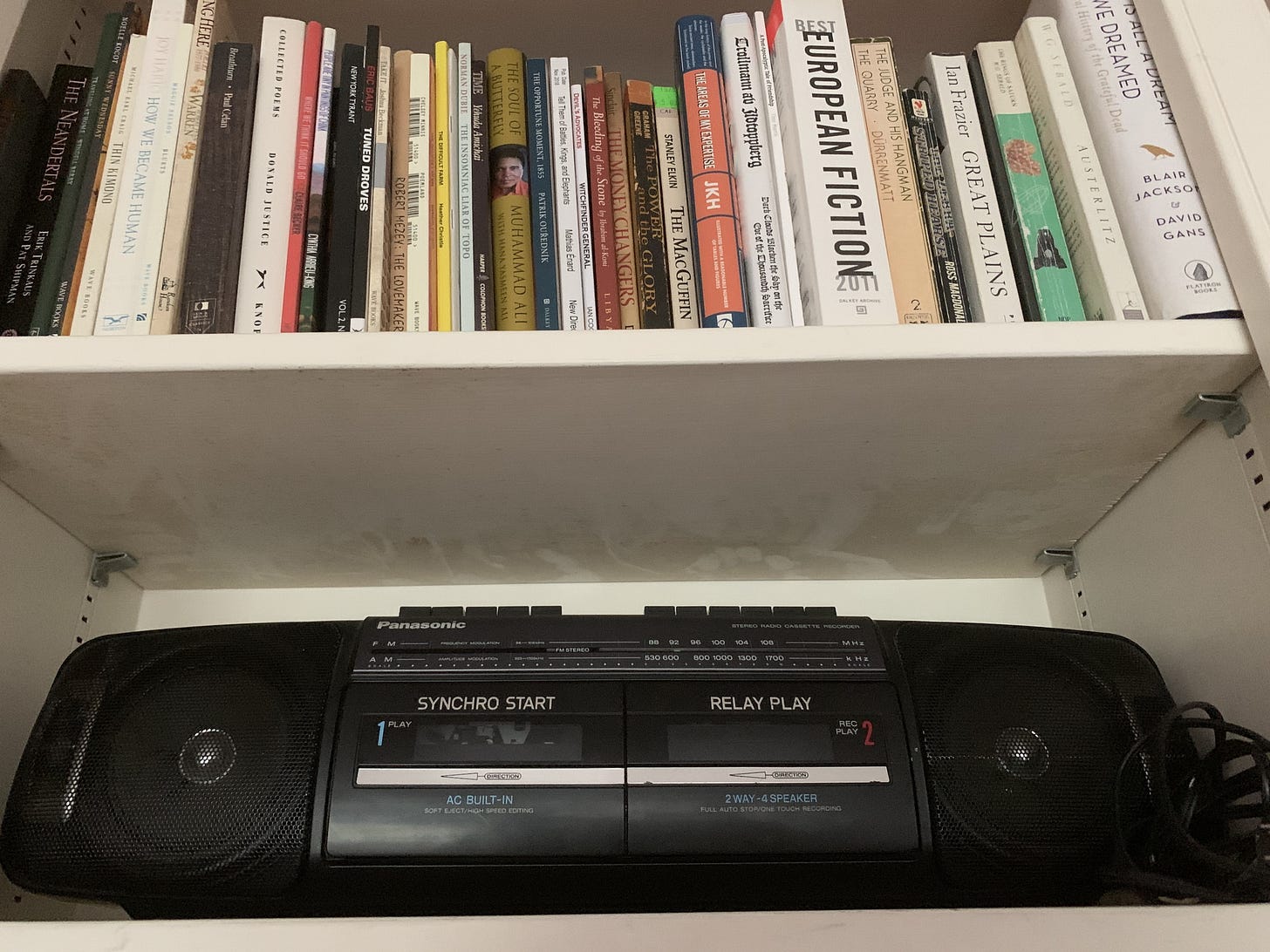

In 1989, John Darnielle (dar-NEEL), a 22-year-old high school graduate from Claremont, California, started recording songs on a boombox that he had bought for about $100 at Circuit City.

The boombox, a Panasonic RX-FT500 dual cassette player, was badly made, but in an interesting way. A grinding noise came from the wheels and was picked up by the oddly placed condenser microphone, so there was a permanent weeeerow, wEEEErow, weeerow in the recordings. Not everybody likes that kind of thing, but Darnielle did. The condenser wasn’t much of a condenser (it didn’t contract its diaphragm at high volumes), so the microphone pretty much unflinchingly accepted whatever was played or sung into it, no matter how loud it got.

He was working as a nurse in the Spanish-speaking unit of Metropolitan State Hospital, a mental health facility in Norwalk, California. At night, in his employee-housing apartment on the hospital grounds, he would write poems, play guitar, write songs, and record.

One night, he was playing a simple chord progression with a bottleneck slide and didn’t have any lyrics, so he picked up one of his poems and started singing it. The song, which he finished and recorded quickly, was called “Going to Alaska.” It went like this:

The jacaranda are wet with color,

and the heat is a great paintbrush, lending color to our lives

and to the air, and to our faces; but I’m going to Alaska,

where there’s snow to suck the sound out from the air.Up, yes, in the branches

the purple blossoms go pale at the edges;

there is moaning in the shifting of the sap, and I see, in them, traces

of last year; but then they hadn’t grown so strong,

and their limbs were more like wires. Now they are cables

thick and alive with alien electricity,

and I am going to Alaska, where you can go blind

just by looking at the ground; where fat is eaten by itself

just to keep the body warm.Because from where we are now, it seems, really,

that everything is growing in a thousand different ways:

that the soil is soaked through with old blood, and with relatives

who were buried here, or close to here, and they are giving rise

to what is happening. Or can you tell me otherwise?

I am going to Alaska, where the animals can kill you,

but they do so in silence, as though if no one hears them,

then it really won’t matter. I am going to Alaska!

They tell me that it’s perfect for my purposes.

In the recording, you hear a TV in a room with old-couch acoustics, then the loud sound of slide-on-strings, and then Darnielle’s voice, with almost no space around it, so that it sounds a little like the room is singing with him. The boombox grinds along; every now and then it squeezes all of the sound into one stereo channel. The slide zooms up and down the neck, making brief stops at the fifth and seventh fretlines. Toward the end of the song, after Darnielle stops singing, there’s a rhythmic whacking noise. Then the guitar falls silent, the TV becomes audible again—it’s an old episode of Hawaii Five-O—and the stop button on the boombox is pressed.

It changed Darnielle’s life. “It sounded good to me,” Darnielle says in a 2010 interview, “really different from stuff I was listening to. So I moved all my poetry-writing energy over into songs.” Sometime in 1991, he came up with the idea of a band called the Mountain Goats, as if to account for what he was hearing in “Going to Alaska.” The Mountain Goats were, in his mind, a band whose songs were characterized by this-is-what-I’ve-got musicianship and high levels of poetry-writing energy. Their songs didn’t sound good in a conventional sense—they were recorded with a flat, attacking treble and almost no bass—but there was a really different feel to them and he liked it. He wrote and recorded more songs with that feel, occasionally repurposing his poems as lyrics but mostly writing straight to song. Toward the end of 1991, a guy who ran a very small label in Claremont released twenty copies of a cassette tape of Mountain Goats songs, under the title Taboo VI: The Homecoming. “Going to Alaska” was on it, along with songs like “Running Away with What Freud Said” (Same morning, world breathing/Far, far from home/Big ringing in the bones) and “Ice Cream, Cobra Man” (I have a glass/Filled with water and light and I feel good tonight). They were all little experiments, some of which worked and some of which didn’t. In each of them, though, Darnielle was figuring something out, or at least reaching toward something, and he was learning to trust, more and more, the feeling that was making the whole thing possible.

He started playing shows; he would say, when he stepped behind the mic, “Hi, we’re the Mountain Goats.” New recordings, either cassettes or 7” vinyl EPs, went on sale every few months: The Hound Chronicles in summer of 1992, Songs for Petronius at the end of the year, Chile de Árbol and Transmissions to Horace in summer 1993, Hot Garden Stomp in the fall, Philyra at the end of the year. Other people joined the band; singers (the Bright Mountain Choir, for a little while), bassists (Rachel Ware, who was also in the Bright Mountain Choir, then Peter Hughes), electric guitarists and keyboard players (Franklin Bruno, off and on), drummers (session musicians, in the early 2000s, then Jon Wurster), and a multi-instrumentalist (Matt Douglas). In response to those lineup changes, and to Darnielle’s aesthetic restlessness, the Mountain Goats’ sound kept turning itself over. What held it all together was Darnielle’s full-bore commitment to the basic problem of writing—making something appear where nothing had been—and, eventually, to the even bigger problem of what he was finding himself writing about. On the early cassettes and EPs, and on the first three full-length CDs—Zopilote Machine (1994), Sweden (1995), and Nothing for Juice (1996)—the Mountain Goats’ songs are mostly dramatic monologues, voiced by imagined people. But the process of writing, together with the passage of time, gradually opened up places that were closer to home. In the Mountain Goats’ late-1990s recordings and performances, Darnielle’s voice began to acquire new qualities: sometimes it was young and reedy, sometimes it ferociously shook, sometimes it sank to a near-murmur. Something similar was happening in his lyrics: the act of writing seemed to be leaving him open to the incursion of stronger sadnesses, anxieties, rages, and fears.

Then Darnielle’s stepfather, Mike Noonan, died. Noonan, who had married Darnielle’s mother Mary when Darnielle was five, had beaten both Mary and John throughout John’s childhood and early adolescence. In the wake of Noonan’s death, Darnielle started writing songs about those experiences and their aftermaths, many of which appeared on what quickly became the Mountain Goats’ defining album, The Sunset Tree (2005). “This Year,” which has become the Mountain Goats’ best-known song, is from that album, as are “Dance Music” and “Hast Thou Considered the Tetrapod.” The boombox was gone, but the sense of immediacy that it had brought to the recordings was emphatically present anyway, both in the lyrics and in Darnielle’s vocals. You can sense the same basic qualities of earlier Mountain Goats songs—a faith in poetry-writing energies and a trust in the vitality of the simplest song-forms—but you can sense something else as well: an almost alarmingly precise feel for emotional states that most people don’t want to know anything about.

For a little while, the Mountain Goats seemed on the verge of fame. But rock fame was on its way out in 2005 and Darnielle never wanted it anyway. What happened next, and all the way up to the present, is that Darnielle kept writing, recording, and touring with his band, which primarily consisted, post-Sunset Tree, of Peter Hughes, Jon Wurster (2008-present), and Matt Douglas (2015-present). The critical acclaim kept piling up: The New Yorker called Darnielle “America’s best non-hip-hop lyricist” after The Sunset Tree, GQ called him “one of the greatest working writers” after The Life of the World to Come (2009), and Rolling Stone called him “the greatest storyteller in rock” after Beat the Champ (2015). So did the songs: by the end of 2021, the Mountain Goats had released 69 records, including 20 full-length CDs, containing 484 original songs (another 131 unreleased and live-only originals are easily available online).1 And Darnielle hasn’t limited himself to songs: he’s also published a piece of music criticism that’s really a novel (Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality [2008]) and three straight-up novels (Wolf in White Van [2014], which was nominated for a National Book Award, Universal Harvester [2017], and Devil House [2022]). But the level of his productivity, like the level of his fame, isn’t very useful as a metric of significance and value. Darnielle is a beyond-great songwriter. And he is, just as importantly, an icon for many emotionally struggling people, because of the ways in which his songs open themselves up to conventionally degraded states of feeling, such as paranoia, loneliness, shame, despair, vengefulness, and grief. You can feel, if you’re one of those people, almost disintegratingly glad to hear the right Mountain Goats song at the right time—a thing of extraordinary beauty and intensity that seems to have been made with you, or people like you, in mind.

In a 2014 essay, Emma Stanford pretty much perfectly describes what it’s like to have that kind of an encounter with the band. After hearing cover versions of some of their songs, she listened to The Coroner’s Gambit (2000) and All Hail West Texas (2002). “I was disappointed at first,” she writes,

to discover that the actual Mountain Goat had a hard, thin voice and had apparently recorded his songs next to some kind of generator. But I persisted, because I had never before heard anyone describe so simply and vividly what it was like to feel unwell. To experience even hope and joy as pain; to regard your own heart, however foolishly and melodramatically, as a crippled animal. . . . Listening to Mountain Goats albums was like mainlining emotional clarity into my bloodstream.

She listened to them every day for the next four and a half years. “I recognized my own feelings only as they were related to me through Mountain Goats songs,” she writes. And yet it was incredibly hard to say why—not why “a balls-out anthem like ‘Heretic Pride’ or ‘This Year’ would be effective,” but why

so many people—myself among them—develop emotional dependencies on all the ugly little songs about dogs and owls and alcoholic Floridians. Their brevity helps, I suppose; JD doesn’t dick around building harmonies while you’re waiting to get healed. . . . But I think it’s mostly about the breathing room carved out by his metaphors. . . . If you discover that his song about moon-colony organ harvesting is actually about how criminally lonely you felt the first time you made yourself throw up, the obliqueness of this association makes it possible to look almost directly, even almost compassionately, at something that three minutes ago you’d have given anything to disown. Darnielle is in the business of reattaching limbs, gently steering us towards the things we need to feel about the parts of ourselves we need to hold onto.

“If Mountain Goats songs teach you anything,” she concludes, “it’s not pessimism or bitterness or melodrama; it’s loyalty. Not to the people you’ve loved, exactly, but to the fact that you did love them. . . . If you listen to enough Mountain Goats songs you learn that there is a kind of dignity in honoring feelings you no longer have.”

Listening attentively to the Mountain Goats creates a kind of circuit in your mind, as Stanford suggests, a circuit that allows you to approach yourself differently. Every song is at least a little distant from where you are at the moment, and every elaboration of its scenario takes you a little deeper into that other world. The more you play the song, the more that other world becomes a place you can go out to and come back from. From the far end of the song’s circuit, you can “look almost directly, even almost compassionately, at something that three minutes ago you’d have given anything to disown.” And once you’ve done that, you can do it again and again. You can start to feel the things you need to feel about the parts of yourself that you need to hold onto. You can remain loyal to those parts of yourself.

That’s a little abstract, so here’s an actual Mountain Goats song: “Song for My Stepfather,” which Darnielle wrote around the time of The Sunset Tree but never released (he’s played it live nineteen times).

You have got that look in your eyes

In the pinprick place where kindness goes to die

I’ll be six years old next year

You erase meYou’ll be sorry, you always feel sorry later on

When you come around to say so, I will be gone

And in my place, meet my letter-perfect body double

You erase meAnd a few years later, I set out on my own

Learned to take the reins up all by myself

Dug the spurs in clean down to the bone

But all that comes later, now there’s only you and me

And the replica where my body used to be

Go ahead and hit him, he feels no pain at all

You erase me, you erase me

It’s made of everyday materials (there’s only one three-syllable word) and laid out in simple, mostly single-sentence lines. There’s four chords (D-G-A-Bm), downstroked undemonstratively. Everything is focused on the song’s scenario, and in the hushed Philadelphia venue where I first heard the song, that scenario grew in me line by line. The stepfather’s eyes, the total absence of kindness in them, the not-yet-six-year-old boy. A stand-in body that the stepfather will hit and that the boy, in the stepfather’s absence, will gash. But all that comes later; now there’s only you and me. And the replica where my body used to be. “Go ahead and hit him,” Darnielle sang, “he feels no pain at all,” and right then I was not just struck but invaded by grief—for the boy in the song, for Darnielle, for me, and for my older brother, who had died in a bad way a month before, and who had been suffering from hallucinations about his stepfather, who had brutally beaten him when he was young. In the worst of the hallucinations, my brother had run in fear from his apartment, even though he was paralyzed on his left side, and fallen, at the end of the hall, into the elevator, where he went non-responsive and evacuated his bowels. Along with the grief, at that moment in Philadelphia, I experienced a rush of loyalty, the kind of loyalty that Stanford is talking about, a loyalty toward my love for my brother. It was agonizing to feel it, because I was so ashamed of myself for not having done more for him. But I didn’t care. “On the day that I forget you,” Darnielle sings in “Twin Human Highway Flares,” “I hope my heart explodes.”

In the last verse of “Birth of Serpents” (2011), a song about reawakening memories of a vivid, scary times in your life, the speaker is in a room—a bad room, from the old days—and his camera-like consciousness is both registering it in the present and calling it back up from the past.

“Let the camera do its dirty work down there in the dark,” Darnielle sings. “Sink low, rise high, bring back some blurry pictures to remember all your darker moments by.” And then this:

Permanent bruises on our knees

Never forget what it felt like to live in rooms like these

From the California coastline to the Iowa corn

To the rooms with the heat lamps where the snakes get born

Earlier in the song, there had been memory-visions that suddenly clouded, memory-truths that sprang up loudly and nonsensically, and a tunnel leading toward an earlier version of himself that took a bad turn. Now, though, the present-day experiences are evoking dim images of what’s down there in the dark, and it is, however weirdly, a triumph to have them. The song, which is in D major, dives down to an E major (PERmanent BRUises on our—), travels up to an A major (KNEES/Never for-), up again to the tonic (-GET what it FELT like to LIVE in), and then on to the chorus-starting G major (ROOMS like these). It’s thrilling, full of the joy of discovery and arrival, in spite of what he’s remembering. What happened to Darnielle’s persona in the song happened in the realm of irreversible historical events. What it felt like, there in the bounded spaces of those rooms, happened in him. Never forget that, Darnielle’s persona says to us and to himself. That is something I can use, something I have used, unconsciously or consciously, everywhere I’ve been since then. Nobody in their right mind could even begin to imagine that the suffering was worth it, that the ends justified the means. But the feeling-tone at my disposal now is mine; I experienced it, I clawed it back from forgetfulness, and I’m never going to let it go.

The “I” in those sentences is my imagined version of the song’s speaker, which means that it can’t help but be me too. By saying in my own words what I hear the speaker saying—or, more exactly, what the music helps me hear in what he’s saying—I’m inhabiting, again, my version of the events that the speaker evokes. One day I was driving to work, through cow pastures near a mall in western Massachusetts, and “Birth of Serpents” was on my CD player. It was early and bright, and I was traveling between my apartment and my office, where I was going to prepare for my classes. The song was turned all the way up. I had been listening partly absent-mindedly and then Darnielle sang the words “dirty work” and I became almost immediately alert and tearful. I thought something like “oh no” to myself. I already knew the song by heart, so the line “Sink low, rise high” came up in me at the same time that it came out of my car speakers. That was painful too and startlingly clear. When Darnielle’s voice descended a little to sing, “Permanent bruises on our knees,” I could feel it coming. Then his voice rose and hit the stresses—“Never forGET what it FELT like to live in ROOMS like these”—and there it was, a broken-hearted fierceness that I had somehow forgotten about. Oh yeah: those rooms. The circuit of the song was at its far end and the song was giving back to me, syllable by syllable—especially “-GET” and “FELT”—an awareness of my more-than-physical shape. It was like my life was continuous again, like I was something more than the site of brain activity, like I was being carried forward by something more than the current of events.

Adults are expected to present themselves as people who have forgotten, emotionally, that they were once children and adolescents. But all adults are capable of returning for brief stretches to what certain moments in their childhood and adolescence felt like to them. In that moment with “Birth of Serpents,” and in many others like it, I sensed the world—the green fields, the yellow backs of the buildings in the mall—from a very old vantage point within myself. The atmosphere, the sort of musk of it, is bad, bad, bad. But the bad parts of my life are parts of my life; I can’t always separate my existence from theirs, and the older I get, the less I want to. And the wild energies of those vivid early moments are curses, definitely, but they’re gifts, too. (“Once things got chaotic and the glasses started flying within the room and you didn’t really know what was going to go on for the next twenty minutes, you liked that,” Darnielle said in a 2006 introduction to “Dance Music.” “Because it was kind of punk rock, you know. For those hour and fifteen minutes, you didn’t really know, all the rules were broken, for those hour and fifteen minutes, who knows, maybe we’re going to leave, and go to space, you can’t really tell.”) The ultimate problem, for me, is the stagnant present, and I’m always looking around for things that will get it moving again, however bad my initial experiences of those things may have been.

Since 2015, I’ve been using the Mountain Goats to keep my present moments alive—to keep them in motion, future-facing, and (always at least a little painfully) continuous with my past moments. Everybody needs to find their own way of doing that, and there are a lot of artists out there, in every artistic form, that you can use. But if you are, as they say, troubled, and/or if you are highly sensitive to the qualities of words, you really should check out the Mountain Goats. You’ll find yourself in the virtual or actual midst of people who are like you in one or both of those ways. And you’ll have a wide, rolling field of songs to listen to. When I first started getting into the Mountain Goats, the size of that field overwhelmed me, and was actually a bit of a deterrent. That’s why the first thing that I’m going to do in All Hail the Mountain Goats is to publish two series of articles that I hope will help to make the band more immediately approachable for new listeners (and more intimately available to long-time listeners). The first one, an album-by-album overview, is . . .

Thirty Years of the Mountain Goats

. . . and it’s going to consist of the following articles (or whatever they should be called—essays? updates?):

1991-94: Cassettes, EPs, and Compilation Releases

1994: Zopilote Machine

1995: Sweden

1996: Nothing for Juice

1997: Full Force Galesburg

2000: The Coroner’s Gambit

2002: All Hail West Texas

2002: Tallahassee

2003: We Shall All Be Healed

2005: The Sunset Tree

2006: Get Lonely

2008: Heretic Pride

2009: The Life of the World to Come

2011: All Eternals Deck

2012: Transcendental Youth

2015: Beat the Champ

2017: Goths

2019: In League with Dragons

2020: Songs for Pierre Chuvin

2020: Getting into Knives

2021: Dark in Here

The second one is . . .

Twenty Songs to Start With

. . . and it’s going to consist of . . .

20. “Waving at You”

19. “Against Pollution”

18. “Jaipur”

17. “Lovecraft in Brooklyn”

16. “Wild Sage”

15. “Dance Music”

14. “Tyler Lambert’s Grave”

. . . and on down the line.

That’s all that I want to say by way of introduction. Starting next week, I’m going to start posting the articles in the “Thirty Years of the Mountain Goats” series on this site and emailing the articles to the people who sign up for free subscriptions. (Subscribing is easy—the button is below.) I hope you enjoy them! I’m also going to start figuring out how to turn All Hail the Mountain Goats into a resource site (like “The Mountain Goats Wiki,” “The Annotated Mountain Goats,” and “The Mountain Goats Wiki—Fandom”). And I’m going to be working on a series of articles on Darnielle’s novels as well.

Looking forward to all of it,

Geoff

A lot of the people who count Mountain Goats songs come up with a higher total than 615, but I can affirm that as of August 20, 2021, you can listen to 615 songs if you buy the CDs (which you should) and seek out the unreleased songs online. (If you want to keep listening to Darnielle songs after that point, you can start in on the Extra Glenns and Extra Lens.) In a later post, I’ll put out my whole chronological list.

Great writing, exciting to dive into the newsletter!